SCUBA Takes Over Snag Diving on the Columbia River

A Historical Diving Article written by Tory the Diver.

Commercial gillnet fishing on the Columbia River for salmon has quite a long history. Around the turn of the 20th century, many Scandinavian immigrants settled in Oregon and Washington on both sides of the lower Columbia River near the Pacific Ocean. Many salmon fish canneries opened on the shorelines of the lower Columbia River. Fishing communities developed, and many gillnet fishermen and their families grew up and flourished in conjunction with the salmon fishing industry. The Columbia River was the world’s largest salmon producing river system on the planet in 1900.

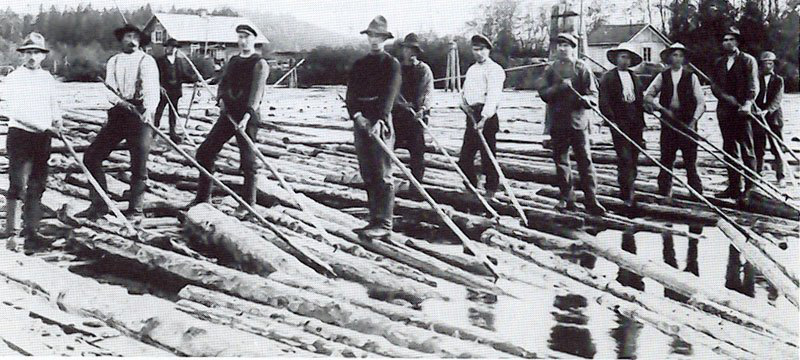

Along with the great fishing industries that developed on the lower Columbia River, the logging industry also developed and flourished. The Scandinavian immigrants pretty much dominated both the fishing and the logging industries. In fact, many commercial gillnet fishermen were also loggers in the off season and vice versa, as many loggers were also gillnet fishermen.

Hard Hat Deep Sea Diving equipment was employed on the lower Columbia River system starting in the 1930’s. Divers were used to clear the gillnet fishing drifts in the river of stumps and various log snags that inevitably ended up stuck in the sandy river bottom after the many floods and high water episodes experienced by the river during the stormy winter seasons and the spring freshet runoffs. Gillnets would catch and snag on the stumps and debris stuck in the sand on the river bottom. These snags had to be removed in order to facilitate gillnet fishing and even purse seine salmon fishing on the lower Columbia River.

Using hard hat diving equipment to remove logs and stumps stuck in the river bottom was a very challenging, expensive and laborious process. A large barge called a “snag scow” was used to support the diver and all of his equipment, including his air compressor, all of his various rigging tools and log tongs, the donkey winch and all of the associated wires and blocks and A-frames used in pulling the snags from the river bottom, and all of the topside support crew, including the diver tenders and the donkey puncher winch operator, and all the riggers dealing with the large snags once they reached the surface. The snag scow was the center of operations in any snagging show on the river.

In the middle 1950’s, SCUBA diving equipment began making its appearance around the Pacific Northwest. It didn’t take long before it was used in the commercial fishing industry clearing snags for the gillnetters.

At first, the old timers were very apprehensive about using the light weight and maneuverable diving equipment for such a heavy and dangerous work like snagging, which really amounts to underwater logging. Many of the old time gillnet fishermen said that the new fangled gear was dangerous and inadequate to handle the rigors of the cold and dark mighty Columbia River waters. They knew for certain that anyone attempting to use such lightweight equipment would be foolhardy and in grave danger of losing his life, should he ever attempt such a dangerous feat.

This type of thinking did not deter some intrepid SCUBA divers who really knew the value of their new type of diving equipment and the great advantage it actually possessed over the conventional deep sea diving gear. These men realized that it would be faster, safer and easier to dive down and attach wire choker cables to the buried logs and snags on the river bottom than it would be to try and do it with the Mark V Deep Sea Diving outfit.

Some of the early SCUBA equipped snag divers on the Columbia River included Tommy Amerman, Bud Sanders, Paul Mark, Teddy Farnsworth, Ed Forsyth, Bill Whitten, Ross Lindstrom and Lou Wellman.

Tommy Amerman broke SCUBA diving equipment in on the snag diving scene in the 1950’s on the old Brickyard Drift, which lies between Portland and Vancouver on the Columbia River near the Portland Airport. He had a small dive shop in southeast Portland, and some gillnet fishermen approached him to see if it would be possible to dive in the high water of the Columbia River during the time of the spring freshets. This is when the river flow is greatest and the high water creates tremendous underwater currents that challenge all activities, not the least of which is underwater diving.

Tommy was known for his tremendous strength and bravado in all types of underwater work using SCUBA equipment. He was able to snag dive for the fishermen in the big spring freshets. They were very successful in removing many snags that disrupted the gillnet fishing operations, and the fishermen were well pleased with Tommy’s performance. The handwriting was now clearly on the wall for all of the old Hard Hat snag divers.

aul Mark broke into snag diving on a drift just upstream of the Brickyard Drift, on the shallow slough that ran along the Oregon side of the river. The water was fairly clear and the current wasn’t as fast as the main channel of the river. It was a perfect spot for Paul to get his feet wet with the fine art of snag diving with SCUBA gear.

Paul took to snag diving like a duck takes to water. He earned the reputation as the best snag diver on the Columbia River. He used many innovations to assist him underwater. He developed an early battery operated underwater headlamp system that attached to the stainless steel band around his face mask. The underwater headlamp allowed him to have at least a few inches of underwater visibility in the river during the spring freshets when the water clarity was notoriously bad. He also developed his own hook-type Hawaiian sling backpack assembly for easy air bottle changes and reduced diver fatigue in the arms and shoulders.

Paul Mark loved snag diving and working for the gillnet fishermen. He later broke into some of the down river drifts, like the Mayger Drift Association, which had over thirty active fishermen during its peak of operation. The old timers were very skeptical at first when Paul started. However, after they saw him get more than twenty snags a tide on a regular basis, they became so delighted that they began clearing new fishing grounds right away! The old hard hat divers were lucky to pull out two snags a day, and that was on a good day.

SCUBA diving equipment was extremely light and flexible and very easy to use underwater in comparison to the archaic, cumbersome and extremely heavy Hard Hat Deep Sea diving equipment. All of the diver’s SCUBA equipment, including his weight belt, weighed less than 75 pounds. The deep sea diver’s equipment weighed 200 pounds. Just the diving equipment weight comparison alone gave the undeniable work advantage to the SCUBA equipped diver over the Hard Hat diver.

Another super advantage that the SCUBA diver had over the Hard Hat diver was being completely self-contained in his equipment. The Hard Hat diver was always attached to the surface and his diving tenders with an umbilical line assembly that contained a steel lifeline cable, a two-way radio voice communications cable and the air hose for his continuous flow breathing supply of freshly compressed air.

The SCUBA diver communicated with the surface by using a series of line pull signals on the choker wire cable that he pulled with him to the bottom. He gave a number of line-pulls on the wire to signal the men on the surface if he needed more line, or when to tighten up the wire once he had attached it to the snag.

The time required for a SCUBA diver to completely suit up and go to work diving was usually less than ten minutes. He could also dress himself entirely without any help from diver tenders. The Hard Hat diver dressing procedure took at least fifteen minutes, and required the assistance of at least two diver tenders to get the diver completely suited up and dressed for work. In the old days, there were at least two men assigned to continuously hand crank the diver’s topside air compressor, providing him with fresh compressed breathing air.

The SCUBA diver would swim down hand over hand, pulling himself to the river bottom and the snag using the special snag net that was used to locate and hang up on the underwater obstruction.

The Hard Hat diver was slowly lowered down to the river bottom by his tenders. The snag scow would anchor upstream of the snag location and try to be directly in line with the fishing boats tending the snag net. These snag net tenders would pick up on the snag net using one fishing boat on each end of the net. They would pick up the net until they were both picked up as close as they could get to the underwater snag lying 30 or more feet deep on the bottom of the river. The snag net attitude tending down from the bow of the fishing boats underwater to the snag was at about a 45 degree angle upstream. The Hard Hat diver would back down stream on his hands and knees until he ran into the snag net. Then he would feel around and find out where the snag was and the best way to hook it up. He had the choker wire attached to his weight belt. He had the river current pushing against him in his big and bulky suit and against his lifeline and air hose communication cable umbilical. The degree of difficulty for a Hard Hat diver working under those conditions was extreme to say the least. Just the pressure exerted on his lifeline umbilical hose by the fast flowing river current made his task virtually impossible. Consider also that he had no light, so most of the time he was working in total darkness. It was really a miracle that the old Hard Hat divers were able to get one snag pulled a day off the gillnet drift. The Hard Hat divers were very tough, strong men.

Once Tommy, Bud Sanders and Paul started working regularly and making good money as snag divers, other SCUBA divers decided to try it, too. Some of them did quite well, while others weren’t too thrilled with the idea of working in dark water and fast current, surrounded by fishing nets that could wrap them up alive. One thing was for sure, the SCUBA equipped diver outperformed the old Hard Hat diver at least ten to one in the snag removal count. Even the old time fishermen came to realize the advantage of SCUBA over Hard Hat divers, and all the fishing drifts changed their methods to completely accommodate SCUBA equipped snag divers.

Gillnet fishing drifts and fishing grounds expanded up and down the Columbia River on both sides between Oregon and Washington states as never before. With the speed and relative ease of removing snags from the river bottom, SCUBA equipped snag divers cleared more of the Columbia River bottom of snag debris than ever before or since. It was all accomplished by the superior diving equipment possessed by the SCUBA equipped divers. The Hard Hat divers that used to snag dive on the Columbia River completely disappeared, just like the dinosaurs of old.

Author’s Note: Having worked underwater with both types of equipment for many years, I will attest that SCUBA diving equipment is at least ten times easier to use in underwater working environments. In the snag diving application specifically, I would say SCUBA diving equipment is at least 100 times easier to work in than Hard Hat diving equipment. I certainly appreciate the great skill and intestinal fortitude displayed by the old Hard Hat snag divers and the tremendous ability they had to even get one snag pulled off the fishing grounds per day. Well done, old timers, well done!